Home & Studio

Front Room

Original Kitchen

Library

Bedroom

Office

Landing

Bathroom

Studio

Documentation & Media

Industrial revolution in Phibsborough.

(Text from Irish Times Life & Style Feature 6 June 2013)

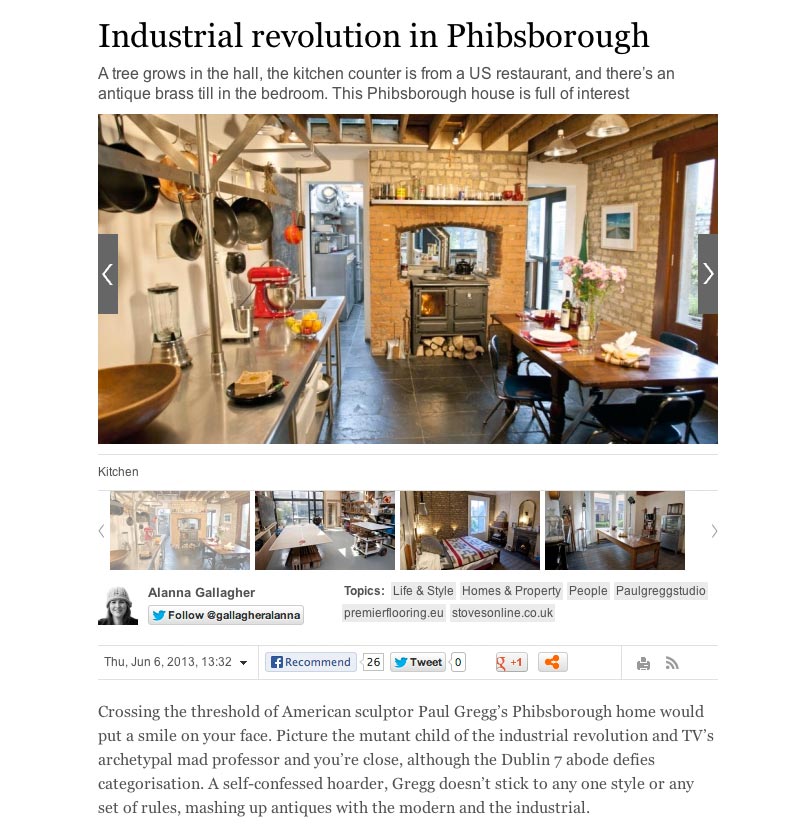

A tree grows in the hall, the kitchen counter is from a US restaurant, and there's an antique brass till in the bedroom. This Phibsborough house is full of interest.

Crossing the threshold of American sculptor Paul Gregg’s Phibsborough home would put a smile on your face. Picture the mutant child of the industrial revolution and TV’s archetypal mad professor and you’re close, although the Dublin 7 abode defies categorisation. A self-confessed hoarder, Gregg doesn’t stick to any one style or any set of rules, mashing up antiques with the modern and the industrial.

He came to Dublin in 1995 as a Fulbright scholar, to be artist-in-residence at the National College of Art and Design. He planned to stay one year.

Instead he made the six o’clock news with one of his art projects, Parachute Mystery, which dispersed full-size parachutes randomly all over Waterford city, making them look like a scientific experiment that had dropped from the sky. The 1998 art attack baffled gardaí.

He bought the three-bedroom house in Phibsborough in 2000, with money from a commission. “I wanted a project,” he explains. “As a sculptor using found objects, I see potential in everything.”

The house is alive with this thinking. In the front room he has a self-styled drum machine, a contraption that houses a snare drum that is part of a series of works designed to give those who interact with them a pay-off. It makes a drum roll sound that is set on a timer that you can adjust – depending on your mood – from a one second soundbite to a super-long, 60-second, roll. One imagines it gets great use at dinner parties.

He loves to entertain. He built an outside barbecue using steel Guinness barrels that he split lengthways, and installed an outdoor bar area that he has only used three or four times in the seven years since he renovated, the lamentable Irish weather simply not letting reality live up to his expectations.

In the kitchen, an Esse wood-burning stove warms the room where on weekends he uses the large table, gifted by an Irish grandmother, to read the papers. The stove has been retired from its original duty, as part of an installation that featured in an exhibition curated by Martin Healy for Cork’s 2004 European City of Culture. It was to show sculpture as an energy loop.

The wood fire heated a steam boiler that powered a steam engine that turned a generator that made electricity to power a digital camera that made a digital image of the fire.

Using a seven-inch diamond grinder, he removed damp plaster from the room’s walls to expose the bare brick and got rid of ceiling plaster to show off the wood beams.

How does he describe his style?

Modern rustic, he laughs, adding; “I don’t like minimalism – for me it’s too clinical.” Instead, he likes materials “left for what they are”.

As well as being an amateur interior designer, he’s also a diehard romantic. He met his wife, Lucia Squadroni, on a Ryanair flight from Bologna to Dublin in 2008. They married in 2011.

In pride of place in his cabinet of curiosities in the den is a music box, a wedding favour that he fashioned and gave to each of the 72 people who attended his nuptials. A snapshot of the couple’s meeting, it features a small tin globe with an aeroplane suspended above it. It plays two songs, the Star Spangled Banner, the US national anthem, and Santa Lucia, a traditional Neapolitan song in honour of his Italian wife.

“My wife and I differ in our tastes,” he admits. “She would like the place to feel more finished.” There are bare boards on the hall and den floors and walls in some rooms have been left as he found them. The end result is darker that we’re told to like,” says Gregg. But it works.

- [x] All

- [x] Commissioned

- [x] Gallery

- [x] Interiors